Towards the end of my tour I had set out to earn my spurs, an old cavalry tradition which signifies you are a cut above. This consisted of three days of physical hazing, meeting with a board of senior leaders to answer anything and everything about Cavalry tradition, and employing skills needed to meet the mission. For example, it could be a scenario where I would use my land navigation skills and find certain points. Upon arrival, the scene was some kind of chaos and you had to act under pressure. Or, it could simply be finding the right terrain to watch convoys and their movement to report back to headquarters. This involved carrying heavy equipment such as packs, radios, water cans and more. Prior to the spur ride they broke us into teams. No one wanted me, the female, on their team. Most of the teams were tankers stationed about 20 minutes away from the airfield. We did not know each other. There were a few aviators in the mix. I was assigned and the sighs were heard from my group as if they were expecting to have to tote me around. In contrast, at the end of the three-day event, the rater who was with our group from the start was absolutely flabbergasted at my performance. I steered the guys in the right direction when they became lost (a skill I learned well as an enlisted soldier thanks to a former commander), carried the biggest guy’s rucksack on top of mine because he hurt his ankle and was always the first to get up when needed. The guys were slow to move and tired. It was, after all, 3 a.m. and they had been through days of physical and mental tests. Upon our return to the endpoint, the chain of command had been made aware of my efforts and I had it a bit easier from there. My team stopped looking at me as a female and began seeing me as a teammate, exactly as it should be.

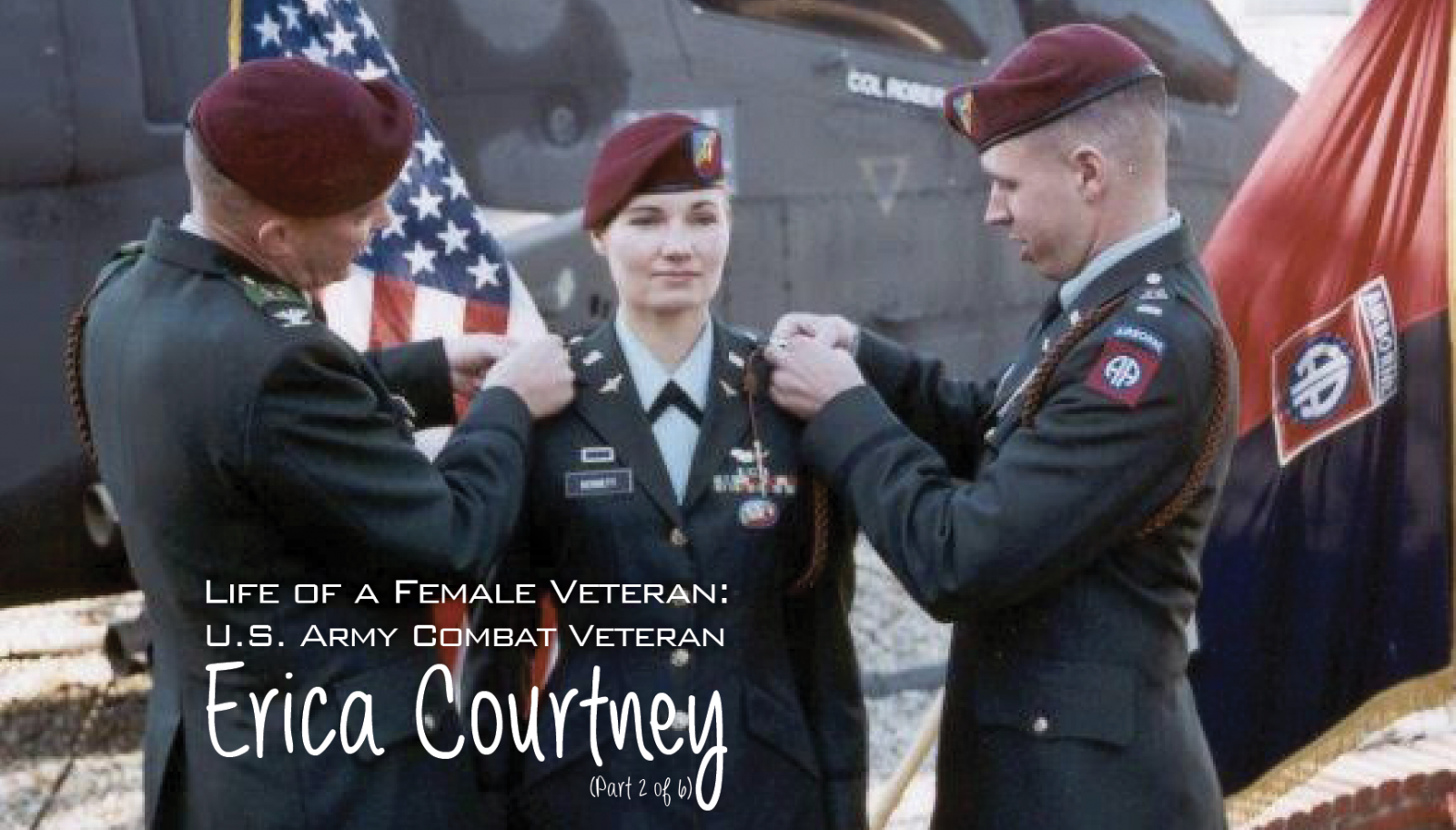

I was awarded my spurs and wore them with pride! One slight issue, women were not allowed to wear pants with their dress uniform, they only had skirts. It was the year 2000 and spurs looked absolutely ridiculous on heels with a skirt. I broke the rules and had a Korean tailor make my uniform pants like the guys wear. This is a big no-no in the service. Uniforms are important and you must stick to the regulation. When I showed up to the ceremony in pants, no one cared. “Looking good lieutenant,” is all I got from my senior leaders. That was liberating. The symbolism here was powerful. Integration is never easy, but it gets easier for those who come after us. We were blazing the trail. I learned early on that if baseless hatred gets to you, they win. I learned to overcome discrimination by working hard, being physically and mentally tough, and setting the example. Eventually, the same guys who did not want me there were the same guys not wanting me to leave. Earned spurs in hand, I left having made it easier for the women behind me and left the unit a better place.

I was awarded my spurs and wore them with pride! One slight issue, women were not allowed to wear pants with their dress uniform, they only had skirts. It was the year 2000 and spurs looked absolutely ridiculous on heels with a skirt. I broke the rules and had a Korean tailor make my uniform pants like the guys wear. This is a big no-no in the service. Uniforms are important and you must stick to the regulation. When I showed up to the ceremony in pants, no one cared. “Looking good lieutenant,” is all I got from my senior leaders. That was liberating. The symbolism here was powerful. Integration is never easy, but it gets easier for those who come after us. We were blazing the trail. I learned early on that if baseless hatred gets to you, they win. I learned to overcome discrimination by working hard, being physically and mentally tough, and setting the example. Eventually, the same guys who did not want me there were the same guys not wanting me to leave. Earned spurs in hand, I left having made it easier for the women behind me and left the unit a better place.

Congratulations, you are going to the 82nd Airborne Division. Wow, okay. I needed a tad of R&R as I was on alert the entire time in South Korea; for a year I was woken at all hours of the night and had five minutes to get dressed, throw on my gear, make it to the airfield and get my helicopter up and ready. No stress there. I went to Australia for a few weeks and became engaged to Chris, a fellow aviator I’d met years prior in flight school. It took nearly the whole two weeks to unwind. At the end of my stay, I became privy to the story of how he got the ring to present. Chris had ordered the ring to be delivered to Korea. Picture this, the FedEx truck pulls up to the gate, in the middle of nowhere, as the unit was on alert with an M1 Abrams tank pointed right at the entrance. Chris had told his First Sergeant (1SG) that if he ever saw a FedEx truck to do whatever he needed to do to get the ring. The 1SG saw the FedEx truck imminently leave and he began running down the road screaming at him to stop. The 1SG accomplished the mission, retrieving the ring and handing it safely off to Chris.

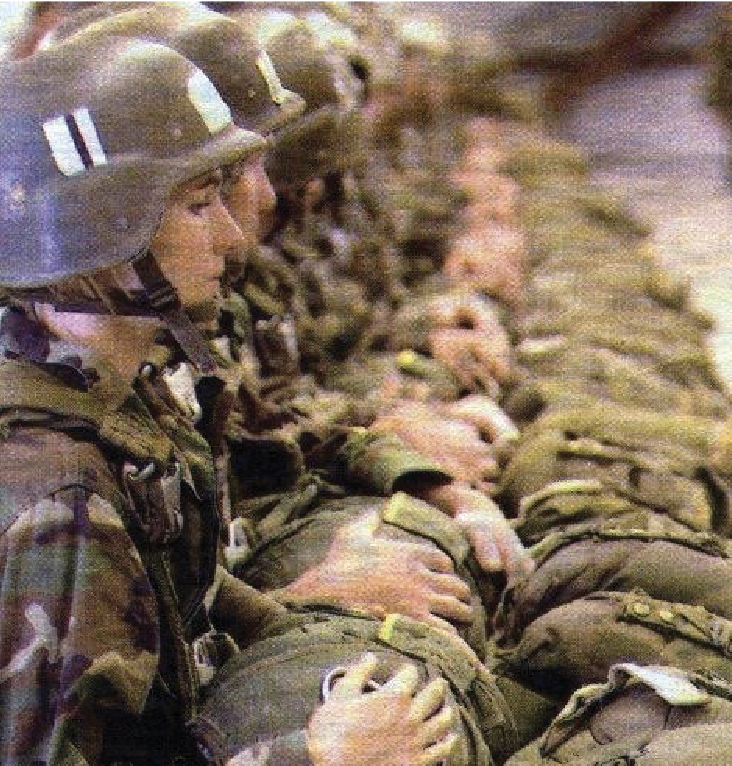

After my R&R, I was off to jump school. Talk about a sore body after two weeks of chilling. As an officer, you must be airborne qualified to be part of the 82nd Airborne Division. I thought it was strange; an aviator having to jump out of a perfectly good airplane? When was that going to happen? I learned that it happened a lot and it was an honor to be sitting next to colonels and privates alike. The Esprit de Corps at that unit was unlike anything I knew. We all had to go through crazy stuff together and it did not matter what you looked like or what your gender was. We are the all American unit. Welcome to jump school. Now do 10 pull-ups before you step over the line and begin your training.

I had the Cavalry brass insignia on my collar versus aviation and that got the attention of many. As usual, a few of the macho men types tried to break me, make me cry. Not happening. The majority of the men were cool, but I had come to expect a certain level of grief for being a cavalry officer, and a woman to boot. Some of the Navy Seals were the most supportive because they knew I could keep up; that was surprising to me. I thought they would be the hardest to win over. However, they are pretty secure in their own skin and appreciate hard work. It is tradition that the highest rank jumps out the door first. Lead from the front. Turns out, in my group, I was the highest ranking. I was what is called the chalk leader. You are standing by the door circling the drop zone and have to stare at the ground and throw any fear you may have out the window. Green light, go. No hesitation.

Scouts always lead from the front. Airborne!

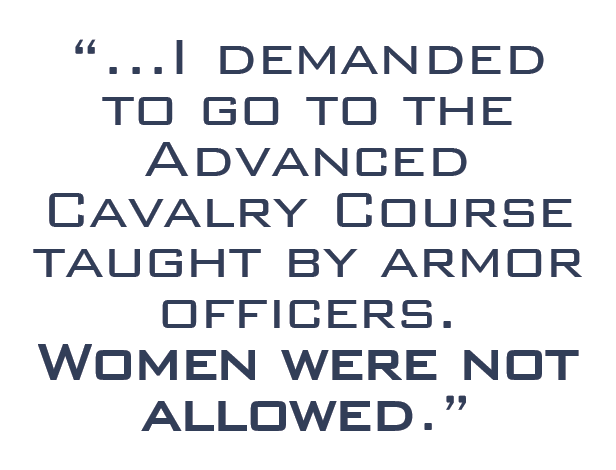

Each unit got easier as my reputation preceded me. Senior leaders wanted me in their Cavalry units. However, at a level above them, so did the Brigade Commander as she was a proficient staff officer who managed 2,500 personnel, $75 million in equipment and over $200 million budgets and contracts. This hurt and helped me. I wanted to fly more and was requested, but kept getting pigeon-holed into logistics and contracts. At each location, there is no way the boss would let me out of the logistics position because I kept the aircraft flying, the unit out of trouble and the soldiers ready. In protest for all my hard work, tactfully, I demanded to go to the Advanced Cavalry Course taught by armor officers. Women were not allowed. After six months of hounding, my boss finally gave in. I was signed up and was Cavalry through and through. I was excited to learn so I could be better equipped to lead my men.

Again, being a bit naïve, I walked into the class and was completely ignored. A young officer grabbed me by the collar, threw me up against the wall and said that I didn’t belong there. None of the other men did a thing. No worries. They did not know who they were dealing with. Instead of whining or stating my case, I understood how to fight fire with fire, how men respond. Physically.

Now, women would not do this, but if you impress men physically, you are in. I reached out to him, grabbed him by the collar, and pinned him on the ground in a position from which he was not getting up. Clearly he did not know that I was an MP and was often used as a demonstrator on how to take a man down despite size. Now I was ready. Physical prowess, check. Mental toughness and expertise was still ahead of me. I ended up teaching half my class how aeroscouts integrate with ground forces because I lived it in Korea. I understood Cavalry tactics more so than most thanks to that assignment. I graduated, got my certificate and moved on. Turns out I was the first female to ever graduate from that school. It was never my intent to be the first, but it kept happening.

September 11th, 2001. A day that changed the nation. I was working in my office with a long line outside my door and got a call that a plane hit one of the towers. Why were they calling me about this unfortunate accident? Little did I know, like the rest of the country, the gravity of the situation.

The second call, “You may want to take a look.” Two planes now each targeting the Towers. What? Okay, let’s turn the TV on. The rest is history.

I slept in my office for two nights straight as the base was locked down. No one knew how to handle something like this. Of course the 82nd Airborne Division was the first to get the call, they are America’s 911 force with the ability to deploy anywhere in the world within 18 hours. As the senior logistician for anything aviation, my world became very busy. Nothing moved in Afghanistan without air assets due to the terrain and scarce roads which were mostly controlled by the Taliban.

Then came my next assignment at the 10th Mountain Division where I was pushing guys out to Iraq, bringing them home and co-managing the effort in Afghanistan. While there, the pace was rapid keeping up with troop demands in the far reaching areas of the country. I had to work with locals, contractors and leaders in order to skillfully get supplies through Taliban strongholds. They were not used to taking orders from women but they were respectful.

While there, I witnessed things most American’s will never have to. The land is littered with landmines left from the Russian invasion in the 1980s. I organized a food and clothing drive for local kids, and while I was distributing the items with a small team, attacks followed. You can’t really trust anyone in a time of conflict. Also, tall mountains made for some hairy flying. Most flight corridors were in between two tall mountains and there were men at eye level (about 7,000 feet) waiving to you with a radio in one hand and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher in the other. It was unnerving to say the least. I was able to determine very quickly that communications were terrible due to terrain and antiquated systems.

Because I worked in contracting, I was able to research state-of-the-art radio systems and pass my request up through the highest levels of leadership in country to get the $20 million in funding to equip all my aircrafts and increase effectiveness. This saved countless lives in the air and on the ground.

While on base, rocket attacks happened frequently. Rest was minimal and when it happened, my wooden shelter was right off the airfield with loud jets and helicopters flying non-stop. If you want to call it lucky, I had to leave earlier than the rest of my unit to bring the other half back from Iraq. It was a fast-moving train of events and you either kept up or got left behind. People forget that every time an aviator straps in their aircraft, things can and do go wrong whether it is training or war. When something catastrophic happens, there are investigations because the Army, manufacturers and family members want answers. I have had to investigate crashes and similar traffic accidents in Germany. It was hard to process, especially if I knew the people. Lest we forget.

Login

Login