Over thirty billion dollars a year is estimated to be lost annually due to elder financial abuse, fraud or scams. Elder fraud is a growing problem, leaving destroyed relationships and economic destruction in its wake. This number is likely higher as according to the National Adult Protective Services Association, only one in about forty-four cases is reported.

Words like “elder” or “elderly” conjure up images of a frail and delicate senior citizen benignly rocking away on the front porch. While it is true that seniors who are most physically vulnerable and who may have cognitive issues are mainly at risk, financial abuse can happen even to people on the younger side of senior: those who are successful, financially savvy and socially connected.

From straightforward theft to slow development through complex relationships, the tremendous loss of wealth incurred by senior citizens results in premature deaths and intergenerational loss of wealth. It ultimately rips at the fabric of society as a whole as trust among family members and faith in financial institutions are destroyed.

From straightforward theft to slow development through complex relationships, the tremendous loss of wealth incurred by senior citizens results in premature deaths and intergenerational loss of wealth. It ultimately rips at the fabric of society as a whole as trust among family members and faith in financial institutions are destroyed.

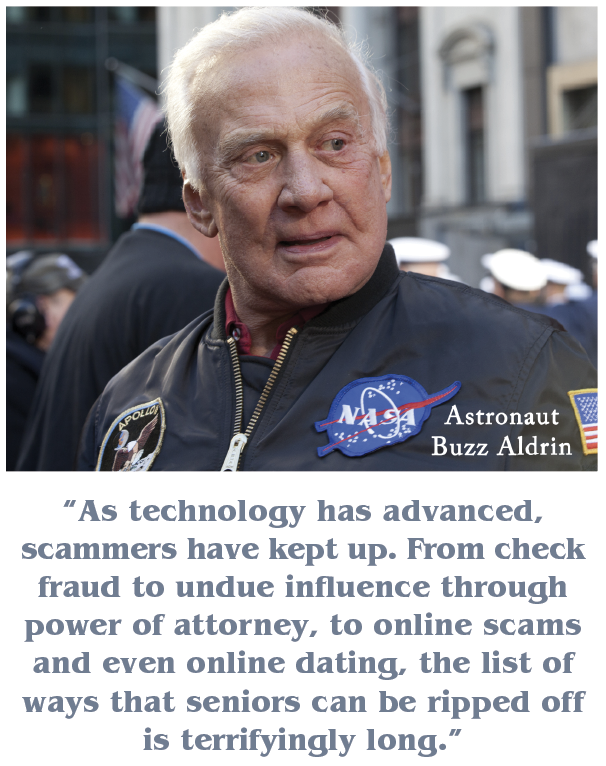

As technology has advanced, scammers have kept up. From check fraud to undue influence through power of attorney, to online scams and even online dating, the list of ways that seniors can be ripped off is terrifyingly long. And as we have seen with cases making the news in recent years, the well-known and well-off—those with the most significant access to protection—are not immune.

From Living Legends to the Lady Next Door, Abuse That Doesn’t Discriminate

Comic book pioneer and former editor of Marvel Comics, 95-year-old Stan Lee, recently made headlines with a restraining order filed against a business manager of his, Keya Morgan. Morgan disputes claims of elder abuse, but changes began to appear in Lee ’s routine, and people who were once close to him found themselves shut out.

Similarly, former Astronaut Buzz Aldrin sued his children claiming they are improperly taking over his finances, while his children assert they are merely looking after his best interest.

Asserting influence, restricting access and isolating a person from their long-term friends and family are all hallmarks of elder financial abuse. Often, it’s not someone from the outside but another family member that becomes the gatekeeper pitting family member against family member.

This idea of undue influence is familiar terrain for Philip C. Marshall, who, in one of the most prominent cases of elder financial abuse, took his father to court over the management of his grandmother’s health and estate. Philip’s grandmother was Brooke Astor, a New York philanthropist who was known for her generosity and support of public institutions.

In a recent conversation with us, Philip recalled it wasn’t the financial aspects of his grandmother’s case that first drew his attention. He began to observe changes out of line with her character and reputation starting with an attempt to sell a painting she had initially bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Philip’s father, Anthony Marshall, financially benefited from the sale, shaving off a commission from the $10 million transaction. Later, he discovered that a series of addenda had been signed by Mrs. Astor who by that time, at over one hundred years old, suffered from dementia. These codicils, signed over many months directed money otherwise earmarked for the charities she wanted to support to his father in the form of cash or to his foundation. “My father used power-of-attorney as both a weapon and shield,” he told us. “By the time the family has any idea, it’s too late.”

However, it’s not only the well-off and well-connected who are at risk from being exploited. Every year, millions of ordinary Americans are taken in by fraud artists, mistreated by a family member or someone who has inserted undue influence over the person’s life.

In a study published last year by the American Journal of Public Health, David Burnes, Ph.D., and a team of researchers conducted a meta-analysis of financial fraud and scams among older adults in the U.S. concluding that one in every eighteen “cognitively intact,community-dwelling” older adults each year is affected by financial fraud. This meta-analysis did not take into account undue influence exerted by family members, but merely outside scam artists.

In a study published last year by the American Journal of Public Health, David Burnes, Ph.D., and a team of researchers conducted a meta-analysis of financial fraud and scams among older adults in the U.S. concluding that one in every eighteen “cognitively intact,community-dwelling” older adults each year is affected by financial fraud. This meta-analysis did not take into account undue influence exerted by family members, but merely outside scam artists.

And just this past February, the United States Justice Department indicted 250 people around the world on elder fraud and financial abuse whose crimes resulted in losses of more than a half-billion dollars from over a million victims. It was the largest coordinated sweep of its kind in U.S. history.

However, statistics can only tell so much. It’s the human cost behind the numbers that prove most chilling.

Marjorie Jones was a financially independent senior woman of modest means who lived alone in a suburb of Lake Charles, Louisiana. A May Bloomberg article details the sad story of this self-sufficient woman who was convinced by a stranger to wire her life’s savings and take out a reverse mortgage on her home. By the time her relatives became aware of the situation, Marjorie had committed suicide.

Baby Boomers Fast Becoming Targets

The ABA Foundation of the American Bankers Association recently released a resource guide for protecting seniors. In it, they estimate that seniors lose 2.9 billion per year due to financial fraud, a much lower number than the upwards of 36 billion per year loss often cited.

The 36 billion number originates from a study by True Link, a company that makes account-monitoring software. While the True Link research was not a peer-reviewed study and the way they defined elder abuse was in the broadest terms possible, Consumer Reports notes the 2.9 billion amount probably grossly underestimates fraud due to underreporting.

The problem of underreporting may change as awareness brings the stigma of reporting abuse to light. With our population increasingly getting older, we literally can’t afford to turn a blind eye. The National Institute on Aging reports average life expectancy at birth in 2011 is 78.7 years and 72 million Americans are estimated to be 65 years or older by 2030.

A good portion of those reaching into their sixties and seventies in the next decade are Baby Boomers born roughly between 1945-1964.

This is a rock n’ roll generation, not a rocking-chair one. Most Baby Boomers tend to not view themselves as “elderly” in the stereotypical sense: they take care of themselves, possess social media smarts and are working longer. Furthermore, as their parents of the Greatest Generation die, a massive generational transfer of wealth occurs, making Baby Boomers even more of a prime target for fraud.

Many may not be vulnerable due to cognitive decline, but are still targeted because of their financial stability and might instead be preoccupied with taking care of their own older parents or sick children. These are adults who can be especially ashamed to report fraud if it happens to them.

Despite the stigma of shame, CEO and President of Women in the Housing & Real Estate Ecosystem, Desirée Patno, felt that coming out about the fraud her businesses suffered at the hands of some financial institutions and an unscrupulous worker is essential to target those Boomers who may be too afraid to say they’ve been manipulated.

She had been victimized by this person who took advantage of her compromised personal situation: at the time the fraud started happening both her husband and her son were hospitalized for different life-threatening illnesses.

In her case, even though she is a successful self-employed businesswoman, her attention was divided. She didn’t anticipate the bank she held her business accounts would fail in oversight, and allow unsigned checks, forgeries and supplement funds through “initiated credit” to perpetuate the stolen funds of over $550,000. Several financial institutions have allowed unsigned checks to be processed in bulk.

Now is the time where cooperation and coordination between advocacy groups, government entities, and financial institutions becomes critical. As the more significant impact of elder financial abuse comes to light and its adverse affect all levels of society, institutions need to take up the call to make reporting and oversight easier.

In their resource guide, the ABA talks about the ability of banks to file SARs or Suspicious Activity Reports with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a division of the U.S. Treasury. Only last year, FinCen and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued a joint memorandum stating underscoring the importance of coordination between financial institutions, law enforcement, and Adult Protective Services.

In their resource guide, the ABA talks about the ability of banks to file SARs or Suspicious Activity Reports with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a division of the U.S. Treasury. Only last year, FinCen and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued a joint memorandum stating underscoring the importance of coordination between financial institutions, law enforcement, and Adult Protective Services.

Starting at age 62, seniors become a federally protected class, and suspicious activity can be reported. Depending on the case, and the bank’s protocol, Adult Protective Services can be contacted. However, this begs the question, what about Seniors who fall just below the 62-year federally protected age?

Financial Abuse = Decline in Physical Health

A vital link between financial abuse and health is becoming increasingly apparent. Mr. Marshall, who gave up a career as a professor to devote himself to the cause of elder abuse full time, talks about the idea of “whealthcare” a term coined by Dr. Jason Karlawish in a Forbes column “Why Bankers, Financial Analysts, and Doctors need to Start Working Together.” On Dr. Karlawish’s website, whealthcare is defined as “a paradigm of merging the banking and financial sectors: wealth + healthcare” and “a strategy to help slow the growth of elder financial abuse.”

A 2016 study by Jaclyn Wong and Linda Waite at the University of Chicago found a direct association between financial and physical health, discovering financial mistreatment indicates more difficulties with ADLs or

“activities of daily living” and increased decline of chronic conditions. The conclusion: financial abuse compromises physical well-being and reduces the chance of independent living in late life.

Next Chapter: Tools for Women

It’s crucial, because of the insidious nature of financial abuse we not only develop awareness but take action: for our parents, our future selves and children.

Women, in particular, are vulnerable due to a longer lifespan and a pervasive gender pay gap. Income women make now has to stretch further later in life.

NAWRB proposes an initiative, Next Chapter, that will assist people over 55 years old to prevent financial abuse before it happens. Next Chapter aims to ensure proper healthcare is in place and assistance from local programs is obtained if needed. Then, seniors can have help reviewing their insurance policies, real estate, and financial portfolios, ensuring the protection of their assets.

As housing industry professionals we care about the well-being of our clients who have a life’s work invested in their home and savings. As community members we care because seniors help enrich our communities; their life-experience and insights add to the diverse voices shaping our society. As family members, we care because it hurts to see the deepest desires of our mothers, fathers, aunts, and uncles destroyed from the outside or the inside. Financial elder abuse is a problem desperately in need of solutions.

Login

Login