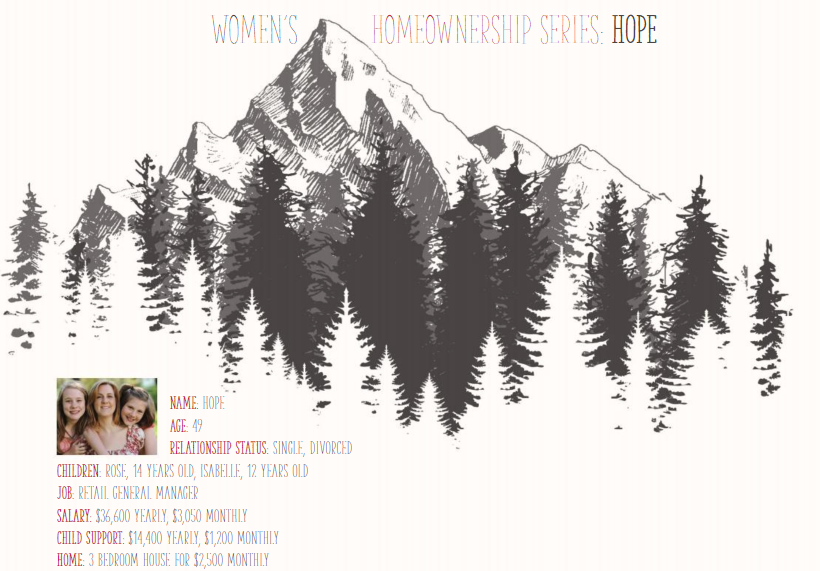

Hope and her husband, with their two daughters, moved into a beautiful 3 bedroom, 2 bathroom home in Boulder, Colorado two-and-a-half years ago. Previously living in a smaller 2 bedroom condominium a few miles away, the family enjoyed the comfort and convenience of a larger space. Their daughters, Rose and Isabelle, were happy to have their own private rooms and a backyard to practice soccer in after school.

Since the couple divorced a few months ago, Hope has taken full responsibility of the $2,500 rent. When she is not busy managing a popular clothing department store, she enjoys spending time with her daughters and painting. She aspires to feature her eclectic paintings in a gallery at the thriving art district in North Boulder, a place she frequents with friends.

Hope has fortified her career with over 20 years of hard work and dedication. Despite not having a college degree, her weekly earnings of $762 exceed that of the average female worker with only a high school diploma. She, however, earns less than the median weekly income of women ages 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Hope’s ex-husband provides $1,200 of monthly child support to help with expenses. Nevertheless, both her income and child support are not enough to continue living at the house with adequate savings for an emergency fund or retirement plan. More than 50 percent of her $3,050 monthly paycheck goes to rent, not including utilities.

Common advice from financial planners is that, at most, a person should spend 30 percent of their income on housing expenses. Hope is already experiencing the burden of not having leftover income to put in savings. With additional living expenses, she only has $200 left every month for unexpected costs and the occasional take-out meal with her daughters.

Living paycheck to paycheck causes Hope tremendous stress over whether she will be able to make ends meet. With her quality of life at stake, she needs to find a new home that better accommodates her earnings. She hopes to find a home in the same neighborhood so her daughters can attend the local high school with their friends, but she soon discovers that houses for rent in her Boulder neighborhood don’t drop below $2,100.

Apartments will have cheaper rent from $1,700 and up, but that will mean a smaller living space. Rose and Isabelle will have to share a room again, which, although manageable, is not ideal for high school girls who have grown accustomed to their own space.

Hope’s situation exemplifies an obstacle facing single women home renters and buyers in the largest American cities. RentCafé reports that out of the country’s 50 largest cities, single women are priced out of rental housing in all but two, Tulsa and Wichita. Denver, just an hour’s drive from Boulder, is one of the cities out of single women’s financial reach. Hope’s problem, like that of many other women, is about gender equality, poverty, and the quality of life for women and their families. As researchers in the RentCafé study found, the median income of men in the 50 studied cities is on average 35 percent higher than that of women. If the gender wage gap did not exist, Hope may be able to keep her current home or afford a different one in her neighborhood; allowing her to maintain the stability her daughters have come to enjoy and not have to potentially sacrifice their quality of life.

Hope has a few options with their own respective benefits and drawbacks. The most obvious choice is for Hope and her family to move into a home in a cheaper city. This way, Hope can pay less for a home that will be similar in size to the one she has now. Although Rose and Isabelle will be disappointed, they can easily keep in touch with old friends and make new ones.

Hope, also, has friends and family that live close by in Boulder, who have been her support system during her recent separation. Even though this family can sacrifice by not seeing their loved ones as much, should they have to? Is it fair that Hope, who has worked and lived many years of her life in this community, be pushed out due to low inventory and high prices?

There are two ways Hope can avoid moving altogether. She could try to get a higher paying job, or she could take on a second job on nights or weekends. Without a college degree, despite her experience and superb work ethic, Hope is limited in professional mobility. Not to mention, finding a new job could take up to six months or longer, which means she will be financially stressed for an indeterminate amount of time.

However, let’s imagine she takes on two jobs. Hope will be bringing more money home, but she will not be there as much. Not only will she have less time available for her daughters, but she will have less time for herself, including her art. What would be the point of working if she couldn’t enjoy the fruits of her labor? According to Huffington Post, lack of sleep, stress and depression are just a few risks of a heavy workload. Many single mothers efficiently work two jobs, but is this the best option for Hope and her daughters?

Hope is fortunate to have options, but none of them are ideal. In situations where single women are faced with unpleasant choices—or worse, no choice at all—we need to help the housing ecosystem create suitable alternatives for them. The first step is to address the issues. By working towards diminishing the gender wage gap, increasing inventory and preserving affordable housing, eliminating the pink tax, and providing homeownership assistance and education, the housing ecosystem can help women cement their economic future.

Login

Login